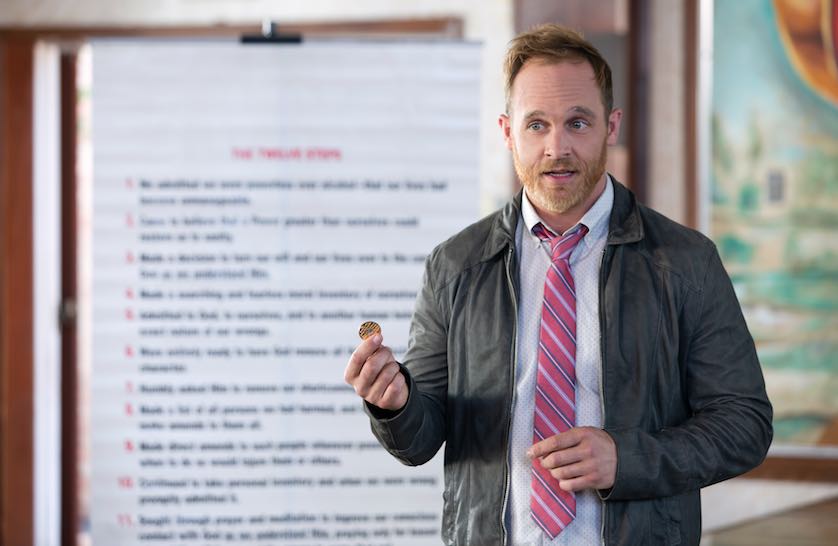

"We need to remove the shame attached to drug addiction," says Ethan Embry.

The 39-year-old actor, who starred in the teen comedy Can't Hardly Wait and currently appears in Netflix's critically acclaimed Grace and Frankie, last month celebrated six years of his own sobriety. But that important anniversary was also met with news that U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions has ordered federal prosecutors to seek the harshest possible penalties for drug offenders.

"It’s ignoring the fact that this is a health crisis. It’s an illness," explains Embry, speaking with Variance about his personal experience just days after Sessions' memo regarding stricter sentencing, marking a reversal from the Obama administration.

While Sessions, who was born in 1946, said last year "good people don’t smoke marijuana," erroneously claiming it's nearly as deadly as heroin, Embry says views like this are "dangerous" and contribute to America's ongoing drug crisis.

"We've criminalized it so much that it keeps people from asking for help and being honest with people in their lives," says Embry, who for about two years was "stuck in a cycle" of addiction to black tar heroin and prescription painkillers.

According to new data compiled by The New York Times, drug overdose deaths in the United States may have surpassed 60,000 last year, compared with 52,404 in 2015, marking the largest annual increase in history as drug overdoses are now the leading cause of death for Americans under 50.

"A big part of the problem is that so much of it is invisible to others," recalls Embry, pointing out that he worked regularly and maintained an outwardly normal lifestyle, while struggling in secret. "A lot of times what happens is, you’re not even getting high anymore—at least, for me. Most of the time, I was continuing just so I didn’t get sick. You’re aware that you’re chemically dependent ... you’re just using to get by."

Embry admits the stigma of drug addiction contributed to his own internal struggle. And he believes so many others are in a similar situation because they're afraid to tell even their closest friends and family members.

"The freedom to admit is so important. That’s the reason it’s the first step in these 12-step programs," he says, noting the positive impact of 12-step programs on his own journey. "This is not just a debate over felonies. It’s literally about saving lives. There are too many people who hide this problem and the ones who love them don’t find out until it’s too late, whether it’s an overdose or a run-in with the law."

Much like Sessions' egregious claim that "good people" don't do drugs, there are many who easily write off addiction as a moral issue, knocking addicts for a lack of willpower or judgment.

Embry knows that's simply not true.

"I’d like to hear from the politicians that are addicted to painkillers," he says. "The law enforcement officers. The clergy. Because they’re out there. And it's not just about willpower."

While celebrities' addiction struggles frequently make headlines, Embry says what's happening in America goes far beyond Hollywood or D.C. And that's why this fight is such an urgent one.

"You don’t lose this many people in one year in a country [to opioids] without it being a widespread problem," he explains, noting prescription painkillers kill more Americans than illegal drugs. "It’s not just our favorite musicians or celebrities. It’s our brothers and sisters and sons and daughters and neighbors. They’re fighting this battle and we’re letting them down."

Quick to acknowledge the complexity of this issue, Embry also believes the pharmaceutical industry needs to be held accountable. "The way they marketed OxyContin is part of why we’re here," he asserts, again nodding to his own experience. "It’s absolutely disgusting and they’ve pretty much gotten away with it."

Photo of Ethan Embry in 'Grace and Frankie,' by Tyler Golden/Netflix

Now the industry has been offering Suboxone as a safer alternative to treat opiate addiction, claiming it can't be abused. And while many politicians and media figures have embraced it, Embry says it nearly destroyed his life.

"I think there are extreme cases where it might be someone's last chance," he says, pausing briefly to maintain composure. "That’s what I was taking—Suboxone—for nearly a year while I was trying to get sober. It’s hard to stop. It's honestly like being trapped all over again because it’s like a 12-hour dose of heroin."

Fortunately, Embry got through what he calls a "very dark time" in his life. But not without eliminating substances completely, including weed and alcohol.

"I definitely got lucky," he says, clearly emotional as he describes his recovery. "I do feel like I got my life back. And you know, I think I'm OK right now. I think I'm in a good place. I just try not to get cocky with it, because it's an everyday thing. But I'm past the point where I let the idea of returning scare me on a constant basis."

"We have these stereotypes, when the reality is, we’re talking about Christian, middle class, union-working fathers and mothers."

Embry believes introducing treatment as the first defense is critical to fighting the drug crisis in America, pointing to former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder's reduction in mandatory sentencing minimums for nonviolent drug offenders as a positive approach.

"It’s still a federal offense if you’re caught with heroin or coke or meth," says Embry. "It’s still a crime if you have pharmaceutical drugs that weren’t prescribed to you. You could still lose your job, lose your family. And I think we’ve got to do better than that. We have to make treatment the first option."

Despite the constant chaos and historically low approval ratings in Washington these days, Embry is optimistic about finding concrete solutions, suggesting conversations about addiction shouldn't fall victim to America's ongoing political polarization.

"I think it can be done, because this is affecting everybody," says Embry. "It's bigger than politics. It's bigger than any administration. That’s why it’s dangerous not to get it right. We’ve been told for decades, ‘These people are bad. These people are criminals.’ So we have these stereotypes, when the reality is, we’re talking about Christian, middle class, union-working fathers and mothers."

Ultimately, Embry hopes the conversation can shift from those in recovery to those who are in the middle of their fight. Citing Prince's shocking death last year from an accidental fentanyl overdose, Embry says until those struggling with addiction feel safe enough to come forward without fear of consequences, the opioid epidemic will unfortunately wage on.

"It's easier for me to say something. I have a great job," he says, taking part in this interview in between production for the upcoming fourth season of Grace and Frankie, a show in which his character is actually a recovering addict. "So my bosses aren't questioning my ability to work, because I have six years behind me. But when you’re in the middle of it, it’s hard to trust anyone. It’s hard to feel safe. And those are the ones whose voices need to be heard." ■